The Neighbors are Watching: From Offline to Online Community Policing in Oakland, California

By Fan Mai & Rebecca Jablonsky, CTSP Fellows | Permalink

As one of the oldest and most popular community crime prevention programs in the United States, Neighborhood Watch is supposed to promote and facilitate community involvement by bringing citizens together with law enforcement in resolving local crime and policing issues. However, a review of Neighborhood Watch programs finds that nearly half of all properly evaluated programs have been unsuccessful. The fatal shooting of Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman, an appointed neighborhood watch coordinator at that time, has brought the conduct of Neighborhood Watch under further scrutiny.

Founded in 2010, Nextdoor is an online social networking site that connects residents of a specific neighborhood together. Unlike other social media, Nextdoor maintains a one-to-one mapping of real-world community to virtual community, nationwide. Positioning itself as the platform for “virtual neighborhood watch,” Nextdoor not only encourages users to post and share “suspicious activities,” but also invites local police departments to post and monitor the “share with police” posts. Since its establishment, more than 1000 law enforcement agencies have partnered with the app, including the Oakland Police Department. Although Nextdoor has helped the local police to solve crimes, it has also been criticized for giving voices to racial biases, especially in Oakland, California.

Activists have been particularly vocal in Oakland, California—a location that is historically known for diversity and black culture, but is currently a site where racial issues and gentrification are contested public topics. The Neighbors for Racial Justice, a local activist group started by residents of Oakland, has been particularly active in educating people about unconscious racial bias and working with the Oakland City Council to request specific changes to the crime and safety form that Nextdoor users fill out when posting to the site.

Despite the public attention and efforts made by activist groups to address the issue of racial biases, controversies remain in terms of who should be held responsible and how to avoid racial profiling without stifling civic engagement in crime prevention. With its rapid expansion across the United States, Nextdoor is facing many challenges, especially on the issues of moderation and regulation of user-generated content.

Racial profiling might just be the tip of the iceberg. Using a hyper-local social network like Nextdoor can bring up pressing issues related to community, identity, and surveillance. Neighborhoods have their own history and dynamics, but Nextdoor provides identical features to every neighborhood across the entirety of the U.S. Will this “one size fits all” approach work as Nextdoor expands its user base? As a private company that is involved in public issues like crime and policing, what kind of social responsibility should Nextdoor have to its users? How does the composition of neighborhoods affect online interactions within Nextdoor communities? Is the Nextdoor neighborhood user base an accurate representation of the actual community?

Researching Nextdoor

As researchers, we seek to contribute to the conversation by conducting empirical research with Nextdoor users in three Oakland neighborhoods: one that is predominantly white, one that is predominantly non-white, and one that is ethnically diverse. We hope to elucidate the ways that racial composition of a neighborhood influences the experience of using a community-based social network such as Nextdoor.

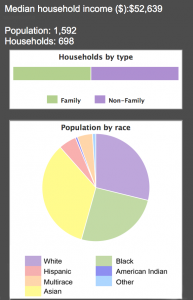

For example, here is the demographic breakdown of one Oakland neighborhood, which we will call Neighborhood 1. As you can see, this area might be considered fairly diverse: many different races are represented, and there isn’t one race that is dominant in the population. It has a median household income of $52,639 and is predominantly non-white, with over half of residents identifying as Black or Asian.

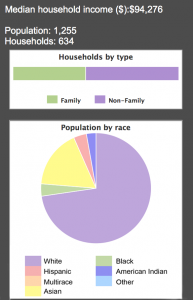

Graphs included in this post were accessed from City-Data.com. Zip codes have been removed to protect neighborhood privacy. These are example neighborhoods, and are not neighborhoods that we are researching.

Now, take a look at the neighborhood that directly borders the previous one, which we will call Neighborhood 2. It has a median household income of $94,276 and is nearly 75% white.

Although these micro-neighborhoods directly border each other, they might normally function as separate entities entirely. Residents might walk down different streets, shop in different stores, and remain generally unaware of each other’s existence. Racial segregation is fairly typical of urban environments in the United States, where people of different racial backgrounds are often segregated into packets of a city that is otherwise considered to be “diverse”—meaning fewer families actually live in mixed-income neighborhoods, and are therefore less likely to be exposed to people who are different from themselves.

This segregation can be disrupted when a person joins social networking websites like Nextdoor.com. Since early 2013, not only can Nextdoor users receive information generated from all people in their neighborhood, but they can see and respond to posts in the Crime and Safety section of several “nearby neighborhoods.” Pushing of the neighborhood boundaries amplifies the potential for users to participate in more heterogeneous communities, but at the same time, may increase the anxiety for trust and the chance for conflict within the larger virtual communities.

Contrary to popular belief, researchers have found that the use of digital technologies is associated with higher level of engagement in public and semi-public spaces, such as parks and community centers. Social network sites can be considered as “networked publics” that may help people connect for social, cultural, and civic purposes. But on the other hand, they can also be used as tools for gentrification that divide communities through surveillance and profiling.

What can we do, as researchers and citizens, to address the complexities of online policing in the use of social networking sites?

No Comments