Citizen Drones: delivering burritos and changing public policy

By Charles Belle, CTSP Fellow and CEO of Startup Policy Lab | Permalink

It’s official: drones are now mainstream. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) estimates that consumers purchased 1 million drones — or if you prefer to use the more cumbersome technical term “Unmanned Aerial Systems” (UAS) — during the past holiday season alone. Fears about how government agencies might use data collected by drones, however, have led to bans against public agencies operating drones across the country. These concerns about individual privacy are important, but they are obstructing an important discussion about the benefits drones can bring to government operations. A more constructive approach to policymaking begins by asking: how do we want government agencies to use drones?

Reticence amongst policymakers to allow public agencies to operate drones is valid. There are legitimate concerns about how government agencies will collect, stockpile, mine, and have enduring access to data collected. And to make things more complicated, the FAA has clear jurisdictional primacy, but has not set out any clear direction on future regulations. Nonetheless, policymakers and citizens should keep in mind that drones are more than just a series of challenges to privacy and “being under the thumb” of Federal agencies. Drones also offer local public agencies exciting opportunities to expand ambulatory care, deliver other government services more effectively, and support local innovation.

So what is the role for local government?

Unfortunately, there is a dearth of knowledge about how public agencies will use drones or the questions they must answer in order to minimize concerns before operating drones. This leaves government, citizens, and private industry relying on heroic assumptions rather than good information about how to make public policy. Therefore, elevating the conversation requires taking a step back. Drones are challenging legal precedent and demanding new regulatory standards. The resulting conversations necessitate including local government as a critical stakeholder.

For example, concerns about individual privacy drive many of the discussions at the local government level right now. One of the biggest challenges public agencies face is the erosion of traditional jurisprudence protecting individual privacy. For decades the courts have relied on the altitude of manned aircraft flying over homes to define reasonable expectations of privacy from law enforcement. Drones shatter these precepts because of their ability to fly (and hover) at low altitudes and carry increasingly sophisticated monitoring equipment. Given that most interactions between citizens and law enforcement are at the local level, it’s no surprise that local governments and police forces are taking the heat for these concerns. But for public agencies that are not law enforcement, there is no information on how data might be collected, retained, or how that data might be shared amongst agencies.

Is it time to rethink warrants in a data-intensive society with drones a commonly used tool by government?

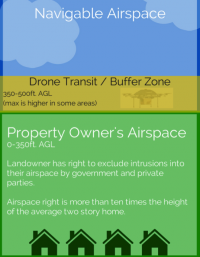

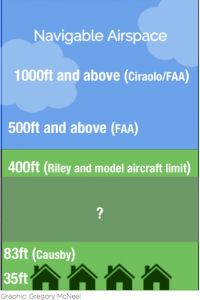

In response, some advocates have pushed for substantive changes to our legal systems; for instance, by proposing the application of property rights to protect individual privacy. The origins of privacy law in the United States can be found in tort law — thank the paparazzi. A shift to a property law framework is likely to implicate local governments since property rights are heavily construed by local law, e.g. through local zoning laws. If rule-makers apply property rights law as a framework for operating drones, cities would (should?) have a major influence on how those laws shape the operation of drones. This framework naturally puts cities on the front lines to litigate many legal issues that will, without a doubt, emerge from the operation of drones by public agencies.

But even if we bracket privacy concerns, the operation of drones by public agencies may conflict with the FAA. The FAA manages the national air space. And large companies such as Amazon and Google are agitating for a sort of drone commercial corridor subject to FAA rule-making: “a one agency to rule them all approach.” To be sure, not everyone supports this approach. Either way, cities have a reasonable argument that at least some degree of the urban airspace should be managed at the local level.

Consider that San Francisco, while not the largest city in the United States, has 50 buildings at 400 feet or taller and more in the pipeline. As autonomous vehicles — air, ground, or water for that matter — become more prevalent, it’s not unreasonable for major cities to explore the extension of their regulatory “roof” to the tallest buildings in the city or even just government buildings.

Visual images of air space management often tend to gloss over an uncomfortable reality: many city buildings are higher than 200 feet (20 -25 stories). (More uncomfortably, this visual ignored Tufte).

Fears stem from lack of information

Protecting individual privacy is important, but that conversation should not be driven by FUD (fear, uncertainty, and doubt). FUD is not conducive to developing informed public policy, which requires data. An evidence-based policymaking approach means putting in place mechanisms that collect data with the objective of making better policy, from protecting privacy to improving building inspections.

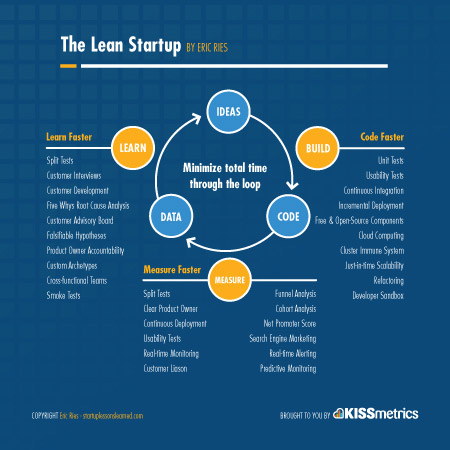

A more effective approach to policy development would have local policymakers emphasize the generation of expertise, knowledge, and public input. Just as startups often use The Lean Startup methodology for product development, governments can use a similar approach for policy (see image). For example, a city might use one agency to test the operations of drones in real world situations, with metrics to evaluate success/failure, and iterate on those lessons to expand testing slowly until a body of knowledge and internal expertise is developed. As of now, there is too much we don’t know about the operation of drones by public agencies to make informed decisions.

It might be a bit gimmicky, but that doesn’t mean it’s wrong.

Society shapes the technology we want.

As we feel our way through the new challenges and opportunities drones introduce, we must consider how public agencies should use drones for the public good. Assuming that government has a role to play, it makes sense to study how public agencies will use drones in order to flesh out our understandings of the implications of those tasks. Erecting bright line rules today might make us feel accomplished, but they are not very useful for a well governed society navigating new technologies. Society should be reflective about technology in order to craft the world we want, not react to the world we are afraid of.

And just because it’s cool.

Bradley Johnson

February 17, 2016 at 7:00 amWith the advancement and improvement of the drone technology, there are so many opportunities that can be exploited. For example the rampant wildlife poaching in Africa can be minimized if not completely done away with if the agencies used drones to do real time monitoring of the vulnerable animals like rhinos and elephants.